Musings

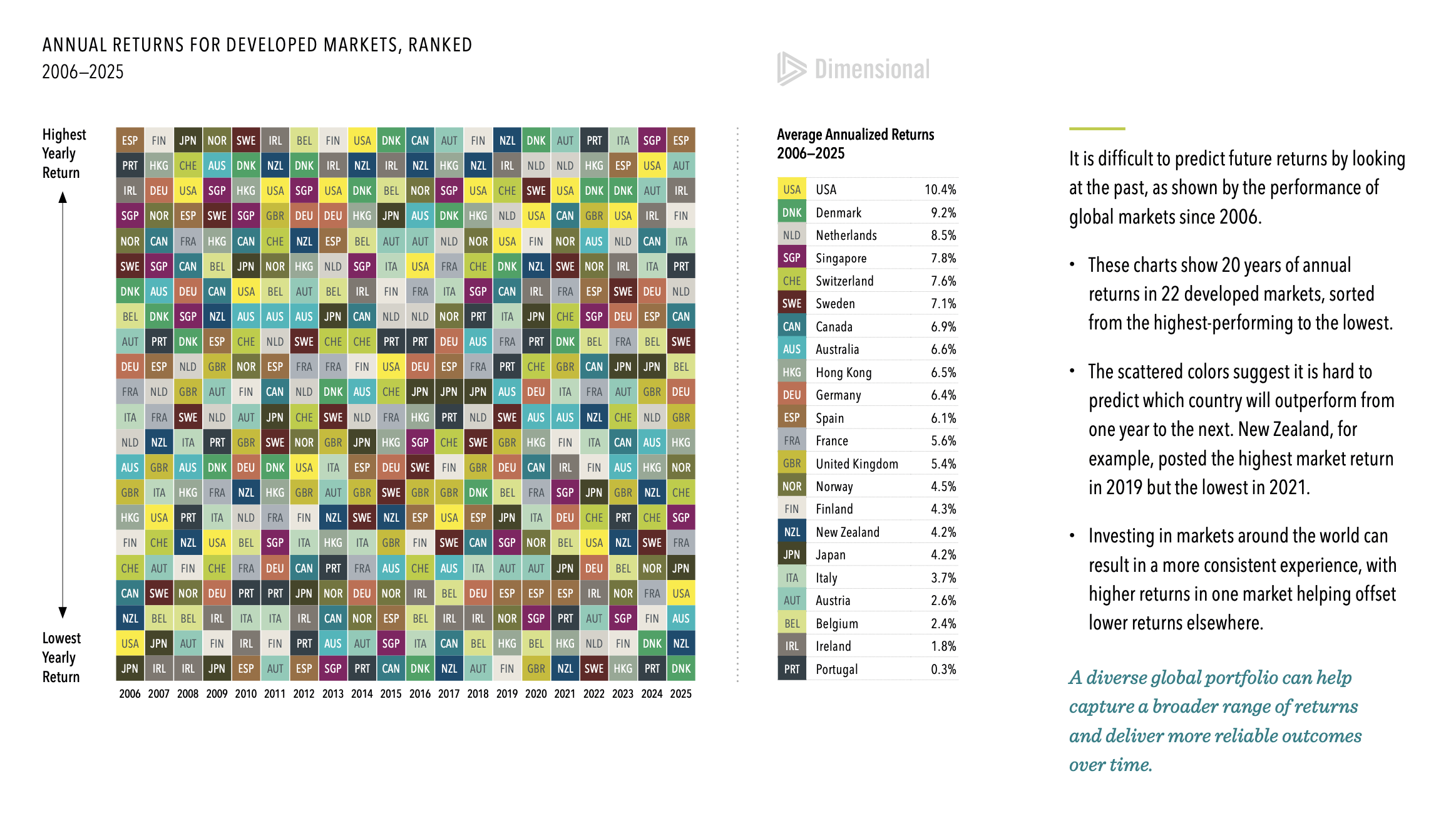

The Randomness of Global Stock Returns

It is difficult to predict future returns by looking at the past, as shown by the performance of global markets since 2006.

Dimensional Crosses $1 Trillion in Global AUM

On February 6, 2026, Dimensional reached $1 trillion (USD) in global assets under management. As we mark this milestone, we want to express our deep gratitude for the trust you’ve placed in us as stewards of your assets.

Why Prepare When AI will Take Care of Everything?

Should we all stop bothering to save for the future? Really? That sounds like a crazy idea, but it’s been proposed by none other than Tesla chairperson Elon Musk, in a recent podcast.

If You Think the Dollar is Weak…

How would you feel if an international financier offered to buy the coat off your back for 89,556 Lebanese pounds, or 42,112 Iranian reals? Would you jump at the offer? You shouldn’t. Those happen to be the two weakest currencies in the world today, and the mysterious financier’s offer would translate to a single U.S. dollar.

AI Inflation

The overall inflation rate has settled down to somewhere between 2.6% and 2.7%. But an unsettling trend might be building higher costs into our economy in two fundamental areas.

2026 Key Financial Data

Our team at Optimus has assembled key financial data worth knowing for 2026. You can download the file here.

The Alts Hype Machine

Anybody who reads the Wall Street Journal lately will have noticed something unusual: seemingly every other day, the business-related newspaper will feature a special advertising section or large advertisement telling readers to “Think it New”—the slogan for Apollo Global Management’s ‘alternative investment’ expertise. They are told that ‘perspective is power,’ and that the Wall Street Journal audience needs to think past the boring, stuffy stocks and bonds and put their money in the ‘convergence of public and private markets,’ aka ‘the future of finance.’

Bitcoin Woes

Cryptocurrency investors are feeling the pinch these days. Two months ago, Bitcoins were selling for $126,000 apiece, riding an investment boom spurred by new exchange traded funds brining a fresh group of investors into the market, plus Trump Administration policies favoring all things crypto. In the wake of these storm winds at the back, crypto investment firms have sprung up, offering professional management in electronic tokens.

Dark Days for the Dollar

A dollar just doesn’t go as far as it used to. That’s what people say about the relentless impact of inflation, but lately it’s been true in another sense. The greenback’s buying power has recently been falling compared to pounds, euros, yen and other monetary regimes.

2025 Year-End Investment Report

Another positive market year is in the books, marking the third year in a row for investors to be grateful for what the markets delivered.

Layoffs Under the Radar

On the surface, the U.S. unemployment rate looks reassuring, at 4.4%. But behind the relatively low number, it’s possible to identify some potentially troubling signs of weakness.

The Big IPO Kahuna

Veteran investors and insiders have always harbored a bit of skepticism about the initial public offering (IPO) market, where brokerage firms hype up the ‘opportunity’ to ‘get in on the ground floor’ of companies where the actual ground floor was long ago when the private firm was founded. Hefty commissions are involved.

Post-SAVE Options

The Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan seemed like a great program for people who graduated from college with large piles of student debt. An estimated 7.7 million student loan borrowers are currently enrolled in a program that exempted them from having to pay principal and interest on their loans if their income was below 225% of the poverty line, and offered affordable repayment amounts based on higher income levels

Upstream Tax Planning

For most Americans, estate planning involves determining how to transfer your accumulated wealth to the younger generation, either through annual gifts or through your estate (or living trust if you want to avoid probate). But some tax professionals are recommending that some of their clients gift assets to their parents.

Uneven Unemployment

The second-most-closely-watched statistic by economists (behind the inflation rate) is the unemployment rate—and right now that figure is a reassuring 4.3%, up slightly from 4.2% over the previous months.

The Health Factor of Your Financial Plan

This is the time of year when choosing next year’s healthcare insurance takes center stage—especially so now, because of the uncertainty around the premium tax credits that millions of people rely on.

Private Equity and Crypto Rejoice

The Department of Labor appears to be giving a bright green light to private equity investments and crypto options in our nation’s 401(k) plans. Both industries have long salivated at the idea of gaining access to the trillions of retirement plan assets, but there was always a tricky barrier: the rules of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, more commonly known as ERISA.

Our Moderation Economy

There’s nothing to worry about in this number: the inflation rate rose from 2.5% to 2.7% in July, which is above the 2% target that the Federal Reserve Board is targeting, but clearly far more moderate than some of the dire predictions around the tariff increases. It’s worth remembering that three years ago, during the aftershocks of the Covid epidemic, the consumer price index had risen from 1% to 9%. The economy has been (as the chart shows) recovering from that bout of inflation first quickly, now more gradually, and this appears to be a blip on the chart.

Investing Glad and Sad

They tell the story of a group of young men in a far-off land who sincerely wished to become wealthy. Accordingly, they traveled deep into the woods to visit an ancient hermit who was said to have mastered the mysteries of magic.

Life Insurance: A Primer

When most people think about life insurance, they think about one thing: money for their family when they pass away. And yes, that’s important. But life insurance—certain types of it—can actually do a lot more while you're still alive.